Doctors at the Royal Free Hospital (RFH) have identified a biological marker which can help them predict whether a patient is likely to reject a donated kidney.

The findings, which have come about as a result of a research collaboration between medics in the US, Leeds Teaching Hospital NHS Trust and a team at the RFH, mean that in the future doctors should be able to provide better management of patients’ medications and improve long term kidney transplant outcomes. This will depend on whether patients do or don’t have the biological marker at the time of the transplant.

Patients who receive an organ transplant must take immune-suppressing drugs in order to prevent their immune system rejecting the donated organ. Professor Alan Salama, a renal consultant at the RFH who co-authored the study, said the findings would help patients with the biomarker by enabling their healthcare team to adjust their medication to prevent rejection rather than having to treat it once it had already happened, but it could also mean that those patients without the biomarker could potentially receive a lower level of immune-suppressing drugs.

He said: “Studying samples which had been collected before and after transplant surgery in the UK and the US, we were able to identify a biomarker which corresponded with patients at high risk of renal transplant rejection – this was with around 90% certainty.

“Until now we haven’t had a way of predicting outcomes and as a result have only been able to be reactive and try to intervene once the rejection occurs. To date, despite taking standard immunosuppression therapy, a small proportion of patients still develop rejection, which has implications for the long term survival of the transplant.

“Now, identifying this biomarker in patients will potentially allow for the introduction of pre-emptive therapy in the form of additional immune-suppressing medication.

“Conversely for those at low risk of rejecting the organ, we could consider reducing the amount of immunosuppressants. This would reduce the risk of developing an infection, which are commonplace following a transplant operation. We now need to simplify the test, which is in the form of a blood test to more rapidly identify those with the biomarker.”

Prof Salama added: “Customising therapies is something we’ve always aspired to - instead of a one-size-fits-all approach. I am delighted that this research has been the result of collaboration internationally and between different departments at the Royal Free Hospital. Certainly we are now that bit closer to a real advance for our prospective renal transplant patients then we were.”

The research has been published in the Science Translational Medicine Journal.

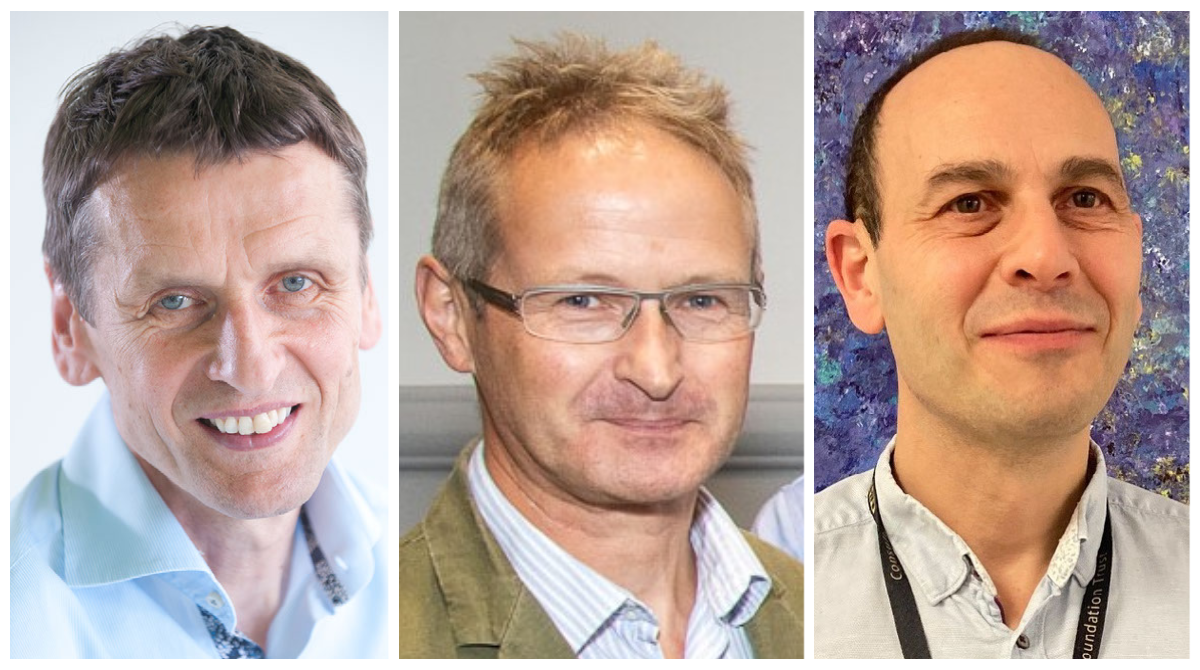

(PIC from L-R - Professor Hans Stauss, director of the UCL Institute of Immunity and Transplantation, Dr Mark Harber, consultant nephrologist with a special interest in transplantation and Professor Alan Salama, renal consultant)

Translate

Translate